CBC News reports, Magna, Stronach deal to go ahead:

CBC News reports, Magna, Stronach deal to go ahead:If you read the comments on this article posted on the CBC website, they range from "what a crook!" to "he deserves his payday". Let me go over a couple of comments below. The first one blasts institutional shareholders:Magna International said Tuesday it will move ahead with a deal worth nearly $1 billion to have founder Frank Stronach give up control over the auto parts giant.

Dissident shareholders opposed to the plan have notified the Aurora, Ont.-based company that they do not intend further legal appeals, Magna said in a release.

A day earlier, the Ontario Divisional Court upheld a lower-court ruling approving the proposal.The dissident shareholders included the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan, OMERS, the Alberta Investment Management Corp. and British Columbia Investment Management Corp.

They had opposed the size of the premium over the present value of the company's shares — about 18-fold — to be paid to the Stronach family trust, and argued it would set a dangerous precedent for similar, future deals in terms of the loss of shareholder value.

The deal provides for Stronach to receive $300 million US in cash, $120 million in consulting fees over the next four years, nine million single-vote shares of Magna and control over a new joint venture focused on electric vehicles.

Shares Rise

Magna shares closed up $3.43, or 4.3 per cent, to $83.04 Tuesday on the Toronto Stock Exchange.

Magna said it planned to implement the change after the close of markets Tuesday.

"We are very pleased with the court's decision and that we are finally in a position to close the arrangement, which has received strong support from Magna's shareholders," Magna CFO Vince Galifi said.

"With the transaction completed, we can refocus on pursuing our long-term growth strategy, including further investments in both innovation and emerging markets, in order to continue to serve our customers around the world."

The institutional shareholders obviously don't like the plan that was approved by 75% of shareholders. This makes them minority shareholders, and they have a tried-and-true recourse - sell their shares and move their money elsewhere. They simply seem bitter that the "big guns" of the giant pension plan don't control what happens to this company. As long as Frank Stronach remains in control, they never will be. The irony is that after Stronach is gone, CPP, Omers, Teachers and the rest can work on buying a majority of shares. If they do that, you can bet the farm they will not be worried about what minority shareholders think...I take issue with this statement because pension funds are by far more long-term in their investment approach than mutual funds or hedge funds. If anything, you'd want to have more pension funds as shareholders to take decisions that are in the best interest of long-term shareholders.

Personally, we need more companies run by individuals. Investment corporations don't care what they invest in - they only care about the money. They sell RIM in droves because record profits weren't high enough, they sell Tim Horton's because the gain from one year to the next was not big enough. We need Carnegies and Fords and Gateses, who care about the company they started and don't run for greener pastures at the drop of a hat.

True, it's individuals who start companies and grow them, but once they pass a certain critical mass, these companies become behemoths and there is nothing that suggests to me that pension funds do not act in the best interest of all shareholders. In fact, it's quite the opposite.

To highlight this point, the second comment that struck me on CBC's website took issue with Canada's dual voting shares:

"75% of shareholders voted in favour of the deal". Does that include Frank's votes which are worth 51% of all shareholder votes? Democracy in action...Opposition to dual-class shares has been growing in recent years. In August 2005, Tara Gry of the Canadian Library of Parliament wrote an excellent comment on dual-class shares and best practices in corporate governance.

By far the simplest solution would have been for the Canadian securities regulators to outlaw dual voting shares, as is the case in most other civilized financial constituencies. Why does Canada permit this abusive malpractice?

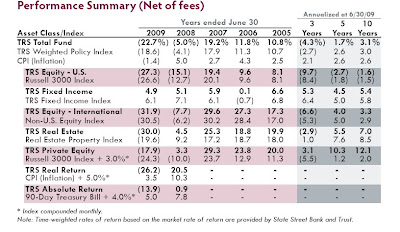

More recently, the Ontario Teachers' Pension Plan posted a highly critical analysis of the Magna-style dual share collapses, asking whether class B shares are worth $863 million (click on images to enlarge):

Magna’s Class B shares have not traded publicly since 2007. One proxy for their value could be the price the company paid in 2007 to repurchase all Class B shares from holders other than Mr. Stronach in a complex deal involving Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska.

In that transaction, the Class B shares were valued at $114 each, representing a 30% premium over the trading value of the Class A shares at the time. (Teachers’ was a vocal critic of the 2007 transaction as one that was too rich and unfair to the Class A shareholders.) A 30% premium over the pre-announcement trading price of the Class A shares on May 6, 2010, (approximately $64) would be roughly $83 per Class B share, or $63 million in total, far below the proposed payment of US$863 million.

A better proxy may be the historical relative market prices of the Magna Class A and B shares from 2001 until 2007 (when the Class B shares ceased trading publicly). It is interesting to note that the average price premium from 2001 to 2007 of the Class Bs over the Class As was just 4.2%. This can be taken as a clear signal from the market that the value of the Class B shares during that period was effectively the same as the Class A shares. We ask ourselves, what has changed since 2007 to justify such a massive premium?

With these comparisons in mind, it is difficult to understand the basis for the US$863 million payment Magna proposes for Mr. Stronach. We found nothing in the management information circular in the way of a detailed rationale for the proposed payment. We consider this to be especially important given the current value of Magna’s Class A shares (which the Class B shares used to track closely) and the precedent transactions where no premium was paid to holders of multiple voting shares when dual class share structures were eliminated.

In the end, despite opposition from several large Canadian public pension funds, Frank Stronach's $1-billion payday arrived:

Was the payout to Frank Stronach "abusive"? Any reasonable analysis would suggest so, but this battle was lost. While recognizing and appreciating that entrepreneurs like Mr. Stronach are the backbone of our economy, founding companies that create lots of jobs while taking on enormous personal financial risks (see video below), I also share the concerns of institutional investors who feel this decision will set a dangerous precedent for other conversion deals.In all, the payout is valued at roughly $1-billion – an unprecedented 1,800% premium and dilution compared to other conversion deals.

The Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, and other shareholders, like the Ontario Teachers Pension Plan, have fought the plan of arrangement before an Ontario Securities Commission hearing in June, as well as before Ontario Superior Court of Justice earlier this month, and the Divisional Court last week.

They argued the payout to Mr. Stronach was “abusive” and would set a dangerous precedent for other conversion deals.

Ultimately, however, the three-judge Divisional Court panel ruled late Monday that it was satisfied that the plan of arrangement met the court’s “fair and balanced” test, and should be allowed to proceed. They agreed with the lower court that a shareholder vote, in which 75% of Magna’s common shareholders approved the plan, should be given significant weight.

Linda Sims, CPPIB spokeswoman, said the country’s largest pension plan was “disappointed” by the outcome, but would not appeal the decision.

“As an ongoing shareholder of Magna, we intend to engage with the company on its governance structure and practices under the revised ownership arrangement,” she said in an email.

2:17 PM

2:17 PM

febry

febry